A slave-whipper's death is recalled

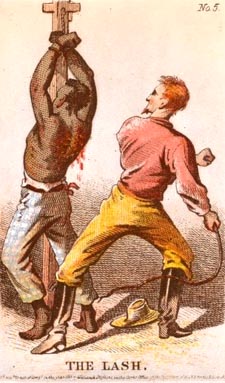

"The Lash," part of a series of 1863 lithographs about slavery shown here.

"The Lash," part of a series of 1863 lithographs about slavery shown here.

August 31, 2015

By Toussaint HeywoodMoncure Daniel Conway (1832-1907) was born in Falmouth, Virginia to a slave-owning family, but eventually became an abolitionist and left the state and the country. He recorded anecdotes from his childhood about a local constable, Capt. Pickett, that are difficult to corroborate but apparently made a deep impression on young Conway. He used the memories and the constable's later fate to create a narrative in his own mind about the cruelties of slavery and redemption afterwards.

Conway told the story several times, but one of the most thorough was in Testimonies Concerning Slavery, London, 1864. He put in context not only the duties of the constable and how his services were used to conceal punishment of slaves in villages, but how village white children were taught to think of slaves. (Paragraph breaks added for ease of reading.)

In the towns and villages the flogging is done by a special and legally-appointed functionary. It is only under severe emergencies or in the heat of passion that gentlemen and ladies beat their own slaves. The gentlemen shun it as a temporary descent to the social grade of the overseer or the constable, as the slave-whipper is called, and the ladies have too much sensibility to inflict complete chastisement; so they merely write on a bit of note-paper, "Mr. -----, will you give Negro-girl Nancy ----- lashes, and charge to account." Nancy, with swimming eyes, waits at the door whilst Madame Serena writes this; takes the billet to the constable's door; waits with a group of boys or coarse young men around her, some of whom jeer at her as one who is "going to catch it," others of whom stand with silent curiosity watching her falling tears, until the grim man of fate appears, leads her in, and locks the door in the face of the idle crowd.

I remember no building in our village so well as the slave-whipper's old, prison-like quarters, built of brick and limestone; and I recall vividly the fascination it had for myself and the other boys. It was known as "Captain Pickett's."

The captain himself, with his hard, stony look, and his iron-gray hair and beard, was the very animal to inhabit such a shell, and seemed to me always as a bit of his own grim house that had taken to walking on the street. I never remember to have seen him elsewhere than walking up and down before the door of his mysterious building; and never heard a word fall from his thin, compressed lips. It was plain that he felt the shadow over him; for the characters who do the necessary but cruel work of Slavery are not pleasantly received by those who employ them. Captain Pickett had no personal connection with the "society" of which he was a most important adjunct; and his children, when their mother was dead and they grew old enough to enter society, abandoned, one by one, their native village, and were scarcely heard of again, so far did they remove from the shadow of the old man's den; and he, grim and solitary, must often have felt that the pangs we inflict, no less than the kindnesses rendered, are returned to our bosoms, heaped up and shaken together.

The respectable family-heads of Falmouth were always particularly strict and careful in forbidding their children any play or loitering in the neighbourhood of Captain Pickett's; and to such prohibited places the eager feet and wide-open eyes of boyhood are as faithful as the needle to the pole.

About this particular building we lingered and peered with an insatiable curiosity, all the more pertinaciously for being so often driven or dragged away. And our curiosity found enough fuel to keep it inflamed; for few hours ever passed without bringing some victim to his door. At this business the captain made his living; and it was by no means dull: he held open accounts with nearly every family in the neighbourhood.

Around each victim we crowded, and when he or she disappeared and the door was shut, we—the boys—would rush around to all the walls, crevices, and backyards which we knew so well, gaining many a point from which we could see the half-naked cowering slave and the falling lash, and hear, with short-lived awe, the blows and the imploring tones, swelling to cries as the flogging proceeded.

Perhaps at that moment some tourist from Old or New England, travelling through the South to ascertain "the facts" about Slavery, is at the hospitable board of the writhing slave's owner, learning how merciful the treatment of the slave is. He will write in his Diary, that, during several weeks passed at the residence of this or that large slaveholder, he saw no cases of severe punishment, though he observed keenly. He does not know to this day, perhaps, that in every Southern community there is a "Captain Pickett's place,"—a dark and unrevealed closet, connected by blind ways with the elegant mansions.

His Diary might have had a different entry had he consulted the slaves or the boys. I have not been careful to defend myself from the charge of hard-heartedness, in that I could, as a boy, seek out and behold without any memorable horror the scenes I have described: the atmosphere around me was not one of any horror at these things.

I remember very well that the tenderness which I, and I believe all other children, felt in early childhood for the Negroes—quite equal in some cases to that felt for our own parents—was considered "babyish" among the boys whom we met in our first ventures on the street; whilst the more advanced boys regarded a domineering tone toward Negroes as "manly." Such aspirations in the young indicate sufficiently what is the fashion among their elders. Moreover, the necessary alternative of not preventing or protesting against a wrong is to become insensible to it.

The slave-whipper is well paid for his ugly work, and makes a "handsome living." But the silent old man of whom I have been writing came at last to prefer no living at all to such a one; for one day a sobbing girl, bearing in her hand an order for forty lashes, was unable to gain admittance; whereupon the neighbours broke down the door, and found that Captain Pickett had hung himself by the side of his own whipping-post.

He had, at least, that sombre grace of Judas; and I have some hope, since finding that his work was odious to him, that, in the lonely den where he stood face to face with Humanity and God, many a blow written in the bond may have been spared.

Years later, writing his autobiography in the 1890s to be published in 1904, he added more ameliorating details about Capt. Pickett:

"It was many years before I could do the poor captain justice. As a matter of fact, the old constable was simply presiding at the last relic of the whipping post. The long dilapidated stocks were still visible near the churchyard, where they had stood at the door of Cedar Church. The whipping-post had hid itself in the constable's office. But I now have reason to believe that in that lonely den many a stripe fell gently, and that Captain Pickett hung himself simply because the shame of being an official negro-whipper became intolerable. The whipping-post ended with Captain Pickett."

He included a footnote:

"A man belonging to a wealthy citizen (Murray Forbes) had to be flogged on some complaint of a neighbour. Mr. Forbes intimated to Captain Pickett his hope that he would be merciful. Pickett said, 'Mr. Forbes, there is not a more tender-hearted man in Falmouth than I am.' The negro told his master, 'Captain Pickett told me to holler, and I hollered, but the cowhide fell on the post.'"

A house said to be Capt. Pickett's, photographed in the early 20th Century. Source.

A house said to be Capt. Pickett's, photographed in the early 20th Century. Source.

He would have been an elected official. Constables were responsible for many tasks and paid accordingly: 30 cents for serving a warrant, 20 cents for summoning a witness, or 50 cents "for whipping a slave, (to be paid by the owner,)."

Stocks and a whipping post were required in each county seat according to Virginia law, but as fines and incarceration became common punishment for free people, they fell into disuse except for the slaves' whipping post.

What seems questionable at first glance is the claim that "few hours ever passed" without a whipping. Stafford County had only 3,596 slaves in 1840, and eliminating those under age 10 brings the total down to 2,330. Many of those would have been in the country rather than Falmouth, but had all their owners used the constable's services, about half the slaves in the county would be whipped in any given year (though some might have been whipped more than once). The percentage would be even greater if confined to Falmouth slaves. The number is high but not impossible.

Another famous paid whipping by a constable was recounted by Wesley Norris after being recaptured by Robert E. Lee: "Dick Williams, a county constable, was called in, who gave us the number of lashes ordered."

The idea of a slave going voluntarily to be whipped seems odd, but in a small town, with eyes on him or her, he or she may have felt no choice, and being caught escaping the punishment would turn out to be worse than the punishment.

The following anecdote from the early 19th Century when New Jersey still had slaves may have been exaggerated for humor, but it corroborates the basic outline of a slave carrying a note requesting his own whipping.

It is related of a town constable, who had charge of a public workhouse in the northern part of New Jersey, that he had a reputation for proficiency in administering the lash to those slaves whom he was called upon to whip. Caleb, a slave, had never been sent to the workhouse for a whipping, but he knew the reputation of the constable.

During the Christmas season his master, who was indisposed, felt called upon to send Caleb to the workhouse for punishment, and he wrote a note to the constable about as follows: "Constable Brown—Please give the bearer thirty-nine lashes and charge to me. Thomas Jones."

Calling up Caleb, Mr. Jones ordered him to take the note to Mr. Brown, who would give him a grubbing hoe. Caleb started toward Mr. Brown's home, adjoining the workhouse, but his suspicions were aroused. He could not understand what his master wanted with a grubbing hoe at Christmas time, and his conscience not being clear of guilt, he suspected that he was to be whipped. Meeting a boy, he took out the note and said: "Massa Bob, what is dis note? Got so many ub dem dis mornin', I got 'em mixed." The boy read the note aloud, and Caleb looked grieved and puzzled. The boy passed on and presently Caleb's face brightened. Seeing a negro boy, he called to him and said: "Boy, does you want to make a shillin'?" "Yep," said the boy. "Well, take dis note to Massa Brown's, an' git a grubbin' hoe, an' I wait here till you comes back, an' den I gibs you a shillin'."

The boy hurried off and delivered the note to the town constable, who took him into the yard, locked the gate, and proceeded, in spite of the boy's protests, to give him the desired flogging, Caleb in the meantime hurrying off home. That evening his master asked: "Caleb, did you get that grubbing hoe?" "No, massa; I gib a boy a shillin' to fotch dat note to Massa Brown, and I spec he got dat hoe."

Let's investigate Constable Pickett himself.

Only one Pickett household appeared in the 1840 Stafford County census, consisting of George Pickett in his 50s, a woman in her 40s, and three white boys in their teens and twenties. In the household also was a free black woman age 10 to 23 and an enslaved woman in the same age range.

By the 1850 census, George Picket (with one t) was 60 years old, living alone except for a 30-year-old black enslaved woman, perhaps the same one grown older. Though that census usually listed occupation, it listed none for him.

Death records are available online for Stafford County beginning in 1853, and he is not included. If he is the man--and he seems to fit--he may have died before 1853. He does not appear on the 1860 census.

Murray Forbes, mentioned by Conway as a slave-owner in Falmouth, owned 13 slaves in the 1840 census.

The few details available do not contradict the broad outline of the story, but Conway himself, as an outside observer, still made Capt. Pickett into a representation of what he wished.